Certianly Uncertain AI

The first rule of Mao is not to tell you about the rules of Mao. Or at least, that is how the card game is played. In this card game, players are penalized for violating hidden rules– and the only way to learn those rules is to infer them from mistakes (yours and everyone else’s). It is a shedding game, where you goal is to get your deck to zero (or the lowest hand if the game stalls).

That dynamic makes Mao a useful sandbox for studying decision-making under uncertainty: players must act with incomplete information, update beliefs from sparse feedback, and balance exploration (testing hypotheses) against exploitation (playing safely). This is exactly the kind of environment I needed for some experiments of the second part of my PhD work.

If you want to just jump straight into the code, a primer on how to set it up and use it is here: https://github.com/kuzushi/mao_simulator

Longer form

How people reason through uncertainty matters; it is a defining characteristic of expertise. The difference between junior operators and senior operators often boils down to sensemaking and discriminating approaches. There is a lot of cognitive science behind all of this, but for the second portion of my work, I needed to understand how one represents those ideas computationally. This is interestingly a double-edged sword in the world of AI. On the one hand, human cognition and learning approaches are well-studied and often underlie many of the algorithms considered fundamental to artificial intelligence. On the other hand, the design of modern AI models, such as LLMs, makes the actual reasoning used at inference to draw conclusions somewhat of a black box.

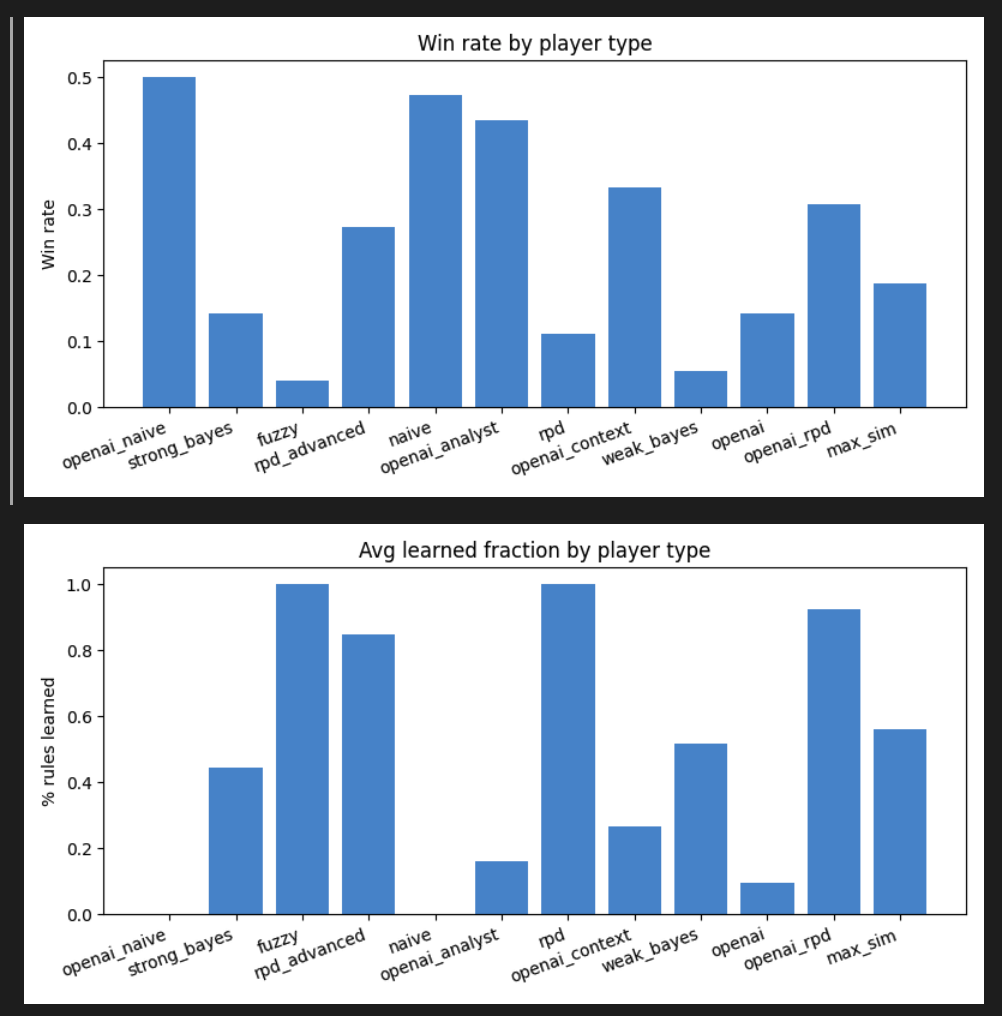

This experiment seeks to bring some of that to the surface, or at the very least, measure cognitive model approaches against each other to see how they operate. The game implements several "players" that represent various approaches to how people may reason about things. These range from Bayesian thinking, fuzzy logic, naive reasoning, and recognition-primed decision-making (RPD). Concepts like Bayesian thinking are well-documented, so in our game of mao, each player represents a known approach. Naive players were implemented at both the AI and computational levels, both of which simply follow the known public rules and YOLO their way through the game. LLM agents were also created with different levels of context to explore approaches that represented more/less thoughtfulness (i.e., with more context) and assess their performance. These are able to use frontier or local models, as you choose.

My particular focus, however, was on RPD-based players, which I implemented using a custom approach. This approach took into consideration previous attempts at fuzzy RPD, multi-agent RPD, and Bayesian RPD. Some of the key factors of RPD are:

- Experience influences pattern recognition (framing of scenarios).

- Ideas are understood through expectancy matching against prototypical understandings/similarity.

- Options are envisioned as they align with plausible outcomes.

- Situations are judged by their normality.

- The first plausible solution that meets the minimal criteria for acceptance is chosen (the goal isn't the most optimal solution, it is about any solution that solves the problem within context)

This implementation attempts a few of these, specifically with regard to framing a problem and evaluating the situation through learning how it is behaving (i.e what rules are being violated). It relies on knowledge of the game (including possible rules) and then updates its own understanding, similar to Bayes, by observing the probability of a rule being active. Subsequently, it plays the cards that fit the pattern first.

Results

As you can see above, the outcome is curious. Players who learned the most hidden rules also lost the most. That seems silly at first, given the idea that knowledge of hidden rules would make you more successful. However, knowledge of the rules appears to have made players less willing to play cards, as they would instead hoard them rather than risk exploration. Furthermore, the player's performance affected the learning. Naive players just play any valid card they have in their hand, which is great from a learning perspective for other players. Whereas players who are less willing to explore often end up with stalemates, where they'd often take a draw penalty and let others suffer the consequences.

This is just a fun experiment; None of the results generated should be taken too seriously. It was/is my first attempt at a computational model for RPD– and it was fun to set up and play. I'd encourage you to play it on your own, but bear in mind being careful about token usage and make sure you set reasonable time-outs in case players stalemate.